J. R. Woodgates

Tag Archives: restorative justice

If the United States released all drug offenders from federal and state prisons, the country would still have the highest per capita incarceration rate in the world — by a significant margin.

Changes are likely coming soon to the laws governing sentencing and mandatory minimums. But how many current and future prisoners will actually be affected?

It was two-and-a-half years between the one time I was interviewed by the FBI in late 2002 about my Internet activities at work and when I received notification from my lawyer that I would face a single charge for possession of child pornography. It was another year after that before I actually stood before a federal judge in Washington, DC and pled guilty to that charge.

Unbeknownst to anyone but a few prayer partners, clergy and family, I had spent those three-and-a-half years going through a rigorous process of church discipline, clinical examination and personal restoration. By the time I stood before the judge, I was a different man from the one who had been engaging in such disordered behavior in 2002. Nevertheless, he convicted me of my crime.

In the fall of 2006, just as I began a nine-month stay in a federal low security correctional institution in North Carolina, I divulged my situation in the parish magazine of my large suburban Episcopal church.* I was overwhelmed by the loving response it elicited. Six months later, I followed up that article with an epistle from prison.

Read both articles now to gain a better understanding of my full story…and the discoveries that inspired me to write Daily Light on the Prisoner’s Path:

* In 2009, having left The Episcopal Church, it became a founding parish of the Anglican Church in North America.

Judge Bennett [considered] the weight of 10 years: one more nonviolent offender packed into an overcrowded prison; another $300,000 in government money spent. ‘I would have given him a year in rehab if I could,’ he told his assistant. ‘How does 10 years make anything better? What good are we doing?’

Nearly half of all federal prisoners are nonviolent drug offenders. Many federal judges who sentence them feel coerced by the congressionally mandated sentencing laws that lock away so many men and women.

This is a long read about one Iowa judge but it’s worth your time:

The voices of the more than 12 million people who annually pass through one (or more) of the nation’s 3,000 jails seem absent from this process. So too are the voices of their loved ones and most dedicated advocates.

Is it really good news that Koch Industries and the MacArthur Foundation, among other deep-pocket entities, are financing prison reform initiatives? Or are they big-footing grass roots reformers?

Kudos to Kairos Prison Ministry International for going after the hard cases, the worst offenders, the guys no one expects to see restored by God.

The wounds of PTSD are similar but different from those caused by moral injury. Both bring a sense of dis-ease and an unsettled psyche. But moral injury results from damage to a person’s moral foundation, caused by willfully immoral behavior – say, shooting a child or raping a fellow inmate.

Long after a return to “normal” life, moral injuries can haunt the conscience and undermine one’s sense of being forgiven. Unless moral injury is recognized and ministered to, it can sabotage a man’s peace of mind.

This article is about moral injury among combat vets. As you read it, consider the same phenomenon as it torments men who have done despicable deeds behind bars and are carrying the guilt of it still:

MORAL INJURY AND THE MAN OF WAR

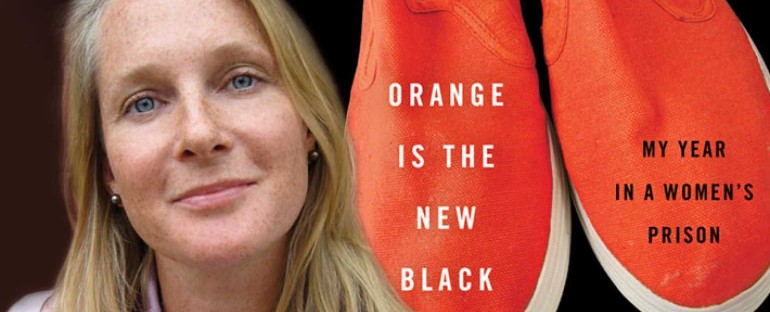

Piper Kerman, author of Orange is the New Black, joins former Prison Fellowship VP Pat Nolan, Senators Rob Portman of Ohio and Al Franken of Minnesota, a Koch Industries spokesman and others, for a refreshingly bi-partisan panel on the current state of prison reform in America.

See how the criminal became committed and the cop changed careers.